At first there was only darkness, emptiness all around. There was nothing to feel, nothing that could be heard. But then she stirred and there was light. The girl’s eyes burned red as the light enveloped her and she was suddenly awake. The bright red light poured through her vision and pulsed into her mind and there was nothing else.

After a time, the girl began to become restless with the light and it seemed to grow dimmer for her until it was no more than a yellow haze, so then she opened her eyes and again the bright light consumed her, but this time she recoiled from it. As she clenched her eyes shut once more, she sensed the first tingling of feeling across her eyes and in surprise she yelped in pain. The feeling slowly intensified as the girl desperately tried to lose herself in it, but then it was spreading and her nerves began to scream at her.

Then there was nothing but pain. A pain that spread from her eyes across her face, through her sinuses to her ears and nose, and then mouth at which she screamed. Slowly, agonisingly slowly, the pain moved down her body consuming her heart and stomach, chest and legs, until she was clenching her fists and flailing her legs desperately.

It was when the pain had consumed her entire body and she was completely lost to it that a new sensation pierced her senses and poured down her arm from a desperate outstretched finger. Not pulsing and hot like the pain, but suddenly cool and soothing, and prickling with a new energy. Like the pain that it followed, the cold, ticklish feeling flowed over her until her skin was enveloped by the swirls of sensation that lashed over her body, making her gasp with relief and delight.

Slowly she moved her finger slightly, causing an ice-cold sliver to roll down her hand and back into her, and she gasped again and the movement caused fresh chills leaping across her chest and down her legs, and she consumed herself to the feeling, feeling which left her writhing with pleasure and gasping with delight at every fresh brush against her skin. The cold soon pulsed like the red hot pain and after a few seconds of blissful agony she collapsed again and lay still.

As her breathing slowed and the pulses of feeling faded away she finally opened her eyes once more; and there was light.

The sun was now peeking over the hills to the east and sending shafts of clear white light down on to the fields, and was caught in the raindrops hiding in the long grass. The lacklustre wind sent the blades gently billowing down across the rolling landscape, flying small patters of raindrops across the sunlight once more. In the coolness of the morning there were even a few spirits of frost hiding and spreading themselves out amongst the shrubbery, but they would run from the sun before too long. The light spirits danced over them singing and laughing merrily as they shrunk back from the heat, and started to sink back into the earth.

Eleanor looked at the world and saw that it was good.

She watched the light spirits for a while; the little glowing dancing figures of bright white which leapt over the fields and chased out the wide eyed creatures hiding in the shadows. One of the fairy-like spirits danced up to her and leapt through her hair and across her chest, and Eleanor giggled madly as the spirit landed elegantly on her knee, bowed, and ran off to follow the rising dawn.

Eleanor sat up gingerly, still smiling from the little shoots of feeling that the cold wind shot across her, but with a considerable sense of relief that it no longer was as strong as it was. Gingerly she tried to stand up, her feet sliding on the wet mud and sending her collapsing forward face first back into the grass. Laughing again, she struggled back up and got to her feet after another attempt.

The world around her filled her senses. The chattering birds in the trees to her left had calmed a little now since the light spirits had moved on, but instead sang their morning songs to the rustling trees. Eleanor looked down to the next field where the early mist still hovered and caught sight of the light spirits dancing round it, taunting the rain for wanting to stay in the bright morning. Slowly she took a few hesitant steps down the hill to the field, and when she was sure of herself, started to run.

Again, she couldn’t help but grin madly as the disturbed raindrops in the long grass splashed against her skin, and as her foot landed heavily in a puddle she caught the cry of alarm from the water spirit she had disturbed. She laughed and ran on, clambering over the fence which separated the fields and falling heavily into the mud on the other side. She shook her head, and took a brief glance at the mix of mud and a little blood that now covered her hands; before laughing at the shooting and fleeting pain and ran on towards the mist.

The light spirits opened up for her as she approached and began to dance round her, encouraging her to join in. Eleanor sprang up and kicked, and pranced, and waved, and sang with the flashing white spirits as the mist retreated before them. Just occasionally she caught a glance at the spirit hiding inside, who was sullenly shouting at the spirits round him and desperately trying to grab its raindrops close to it. After a few minutes the mist spirit finally seemed to admit defeat and fell back to the ground and the light spirits cheered, their high resonant voices echoing around the fields. Their song finished, they then, as one, bowed to Eleanor in thanks and flew back towards the sun. Eleanor bowed back to them and waved as they spiralled back into the sky to find another likely spot for a dance.

Now aching from her exultations with the light spirits, Eleanor wandered back across to the edge of the field and sat down heavily against the roots of an old tree, staring at the wide panorama of the morning. Absent mindedly, she gently plucked a brightly spotted mushroom and squashed it between her fingers, letting the mush slop down her hand.

“Hey!” A sharp voice, almost nasal, directed at her. “Leave that alone!”.

Eleanor rolled over on to her chest and found herself nose to nose with a small gnomish creature with a long green nose and half-buried branch-like legs in the wet mud. She supposed that the little thing, whose hairy ears were flapping in the wind, was rather irritated.

“Why?” she whispered back, and the little creature blinked back at her with deep dark green eyes.

But all this did was to draw a long, protracted stare.

“Are you an Earth spirit?” she asked playfully.

“‘Course I bloody well am, think these shrooms just spring out the ground, do yer?” he replied sharply, and stared at her menacingly. “You’re Eleanor ain’t yer?”

Eleanor shrugged, and plucked up another mushroom.

“Oi!“ the spirit cried immediately. “Stop that! Do you need to kill all me crop as well as getting’ them light spirits all excited and keeping all the water away? We’re not going to get any good mist down ‘ere for bloody ages now!”

Eleanor giggled at him and prodded him with her finger, making him rock backwards.

“Don’t be so picky” she said softly, as the sprit mumbled his disquiet and tried to replant one of his legs.

“Don’t you go proddin’ me, young miss, I was raisin’ acorns before you was even thought of!” Eleanor rolled her eyes, but smiled. “And anyways, there ain’t no call for you to be prancin’ about with all them sparkly bastards and upsettin’ everyone else round ‘ere. And in the all-together too, I don’t know; don’t know what the worlds comin’ to these days, I really don’t. Ain’t anyone told you you was naked?”

Eleanor shrugged. “No?”

“Well you bloody well are!” the spirit yelled back. “Now stop pullin’ up all me shrooms!” And with that, he bent back and thrust his head back into the mud.

Eleanor stayed in the fields for the next few days, persuading some friendly earth spirit to let her sleep in their burrow at night, and eating the mushrooms and fruits that she found in the bright sunshine of the day. Despite the occasional mutter of disapproval from the gnomish spirits amongst the trees, she stayed naked.

The days passed slowly for Eleanor; each morning she would wake up before sunrise and wait for the light spirits to come prancing out from the dawn and help to chase the down the shadows and mists, but by the third day they barely had any opposition. She would then wander around the fields for hours on end, running through the grass, trying to leap over the fences, eating whatever fruit she found or talking to the spirits that love the daylight.

She chatted with the gloomy and smelly water spirits that sat sullen in puddles near the edge of the fields, trying to excite them to chase her; but they never did, and she would always end up stamping on them in frustration. She’d shout at the winds until an air spirit would come down to see her at which point she’d to try and persuade it to take her flying; but the best she ever managed to get would be to get the invisible wisp spirit to whistle through her hair. Occasionally she got a few words from the huge tree spirits, though it was usually only a angry deep grumble for her to leave them alone.

By the evening she would switch sides and club together with the spirits who love the shadows and chase all the light shadows out of the fields, before lying back and staring at the stars, trying to will them down to play with her. But they never did.

The rushing sensations of the first morning never returned to her; but she still felt the world around her keenly, the sun felt hot and comforting and every scrape, brush or cut against her skin would make her yelp and smile. On the fourth day she started to explore a little further beyond the first couple of fields, and in the next one she found a large pond and befriended the bright and welcoming water spirit that lived there. The sprit let her swim and splash for hours, and affectionately cleaned her down and squirted water at her to make her laugh. However by the end of the day the spirit grew weary of her constant intrusion and finally asked her to let his water lie still for a while. In response Eleanor plucked up a particularly disapproving mushroom spirit that had been complaining the whole day long and threw it into the pond, and she left them arguing.

Soon she knew her way intimately around the half dozen fields that covered the little valley. When she caught herself looking outside the fields, perhaps to the lofty hills or to the wall of high hedges at the far end of the topmost field, she would look away again quickly and forget what she had seen.

By the sixth day she had found that she had walked all the way round the fields three times without seeing anything she didn’t already know. Most of the spirits were ignoring her now; the earth spirits were leaving, angry at the constant interruptions at night; and Eleanor followed their slow progress, by paw, by twig, and by tiny claw as they left the fields through a hole in the top fields’ hedgerow. She didn’t dare follow. Even the light spirits and shadow spirits were ignoring her now, annoyed at her constant shifting allegiance each dawn and dusk. By the evening the meadows felt cold and unfriendly, and she was forced to sleep above ground, as all the earth spirits had gone and caved in their burrows after them.

The next morning she awoke hungry, afraid and colder than she had ever felt. The fruits had been finished the previous day, and the only spirits she could see creeping on the fields were skulking frost spirits. Eleanor wrapped her arms around her knees and cuddled herself against the cold, tears quietly falling from her cheeks.

Her mind suddenly felt empty, and the cold blasts of wind that had once excited her now seemed to be mocking her in her weakness. She rolled over, sobbing quietly, and lay back against a barren apple tree, but the roughness of the bark just seemed intrusive and painful to her now.

Her desperate eye caught her own hands, and found them to be skeletal, and weak.

“What’s going on?” she shouted suddenly, and her cracked voice echoed a little in the morning gloom.

It was then she turned and her eyes caught sight of a small spirit the like of which she had not seen before. It was in the form of a small female dormouse, with a small cluster of baby pups around her, but it seemed bold and was watching Eleanor intently.

Eleanor, very gently, lay face down in front of the watching spirit until its twitching nose was no more than a few inches from Eleanor’s tearful eyes.

“What are you?” Eleanor whispered, her words bubbling through her sobs.

“What are you doing Eleanor?” the mouse whispered back, so gently she had to strain to hear it. “Didn‘t you want to know more than these fields?” Eleanor blinked as her tears began to dry up, and then smiled suddenly as a tiny pup lost a teat momentarily before gaping and suckling once again.

“Are you a life spirit?” Eleanor breathed, as softly as she could. The spirit still winced slightly.

“Listen to me child.” the spirit squeaked back. “You are wandering why all the spirits in these fields didn’t want to stay with you. You don’t understand why they would not want to play with you, and look after you. You can’t blame them, they are only doing what they know.” The spirit looked away momentarily to stop a young pup moving too far away.

“But I’m the same aren’t I?” Eleanor gasped, suddenly hearing the panic in her voice. “I’m a spirit of the field just like they are right?” The life spirit blinked and looked at her sadly.

“No, child. You’re much more than that. You’re different.”

“No, I’m not!” Eleanor replied immediately, but her shout startled the pups who cried suddenly. The life-spirit didn’t reply for a few minutes as she calmed her pups, and Eleanor was lost in the gentleness of her care towards her young. Finally the spirit turned back to her.

“Yes, you are, Eleanor.” she whispered, even more quietly than before. “And it is a very special thing that you are. You will always be amongst us but you are more than we are.” Eleanor leaned in even closer so she didn’t miss a word.

“What am I?” she breathed. The spirit appeared to pause for a moment.

“I do not know.” she admitted finally. “But do you not think you should find out? You cannot stay in these fields because you will not be able to stay with the spirits. You are cold and afraid, and you are hungry. And you long for more than these fields.”

Eleanor cried once more when she heard those words as she recognised the truth in them. As fresh tears rolled down her pale and mud-caked cheeks, she whispered desperately;

“But where should I go?”

The life-spirit looked down and shuddered slightly.

“The world is a big place, my child. It stretches way beyond these fields, and it is filled with spirits of all sorts that will be there for you if you want them. But it is not an easy place, Eleanor.” the dormouse added, looking back at her. “Go and find new fields. Stay and you‘ll only bring death, Eleanor.”

Eleanor shuddered at the coldness of her words, but she understood, and nodded.

“So I need to go look for new fields?” she asked, her voice cracking as she still cried.

“You will need to make new fields.” the spirit whispered back. “But before that you will need to know why.”

Eleanor shrugged. “Why what? What does that matter?” The spirit gently started to curl up so her pups were huddled close to her body.

“You will find out I’m sure.” she whispered, so faintly that the slight breeze stole the words away. “Now go. Make your choice. Leave these fields or deny it. You’re dying here, and my pups do not long for that.”

Eleanor’s eyes filled up with tears and she had to pull herself away to wipe her eyes clean. When she looked back the spirit had gone.

She felt it then – the harsh punch of hunger that was hammering her stomach, the fever that pulsed her head, the numbing cold that rendered her fingers and toes stiff. She would have to sweat and work hard for her food after all.

Slowly, with teardrops falling round her, she clambered to her weary feet and looked to the distant hedgerow at the top of her fields. Gingerly at first, she clumsily staggered towards it, clutching her stomach and moaning at her fever. As she walked, rain began to fall from the deepening clouds above her, and it made her slip and fall. But each time she would hear the little spirits in the raindrops whisper encouragement in her ears, so she would get back up and stride forward as fast as she could.

After a lifetime of torment she reached the hole in the hedgerow that the Earth spirits had left by. She slowly bent down and crawled into the narrow hole, and once again she could see light, a different light, from the other side.

Even through the pain Eleanor smiled. She knew that the life-spirit had been right – for fresh fields already lay before her.

The intuitive response of those who are least fond of children is generally an assumption that children are something of a moral vacuum. In this area, there is a huge variation in perspectives of what moral innocence might consist of – the

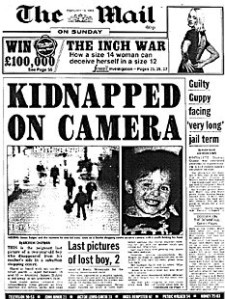

The intuitive response of those who are least fond of children is generally an assumption that children are something of a moral vacuum. In this area, there is a huge variation in perspectives of what moral innocence might consist of – the  For those unfamiliar with the case; on 12 February 1993, Thompson and Venables took James from a shopping centre in Liverpool while his mother was distracted. The boys then walked James over two miles through the streets, being approached by a number of people who they convinced that James was their brother. They led him to a railway line, covered him in paint, savagely beat him and left him to be cut in half by a passing train. The sheer horrific nature of the incident, as well as the ages of the murderers created a media frenzy which rose to a height at the trial. The boys were found guilty of murder and each sentenced to 20 years, originally in a young offenders institution, then later in prison. Even on their release in June 2001, the media were still dogging the case, and Thompson and Venables have since started living under new identities, which then provoked a public outcry.

For those unfamiliar with the case; on 12 February 1993, Thompson and Venables took James from a shopping centre in Liverpool while his mother was distracted. The boys then walked James over two miles through the streets, being approached by a number of people who they convinced that James was their brother. They led him to a railway line, covered him in paint, savagely beat him and left him to be cut in half by a passing train. The sheer horrific nature of the incident, as well as the ages of the murderers created a media frenzy which rose to a height at the trial. The boys were found guilty of murder and each sentenced to 20 years, originally in a young offenders institution, then later in prison. Even on their release in June 2001, the media were still dogging the case, and Thompson and Venables have since started living under new identities, which then provoked a public outcry.